why you still can't trust your financial adviser

With the Fiduciary Rule in doubt, seeking professional advice on your money remains a dangerous proposition.

Illustrator: Josh Freydkis

Published June 7, 2017, 1:00 AM MDT

Your new financial adviser has a well-decorated office, a firm handshake, and a bright smile. After an hourlong meeting, you leave with what you think is a state-of-the-art investment portfolio. You feel financially secure, taken care of.

It’s also possible you’ve made a huge mistake. The White House under President Barack Obama estimated that Americans lose $17 billion a year to conflicts of interest among financial advisers. Wall Street lobbying groups dispute that math—and they’re right to do so. The actual dollar amount is probably much higher.

A wave of research over the past few years has documented serious problems with how Americans get financial advice. Susan Shaffer, a 70-year-old retiree in Narberth, Pennsylvania, learned this the hard way as she hired and fired multiple advisers over two decades. One chose inappropriate investments, including small-cap stocks. Another put her into funds with huge, back-loaded fees. The third promised to charge just $500 a year, then stuck her with thousands of dollars in commission costs.

Each time, Shaffer did her own research. She took classes, pored over dense account statements, and generally did the work she was paying her adviser for. “You have to keep watching everything. You’re very vulnerable,” said Shaffer, who retired three years ago after a career in the pharmaceutical industry. “Nobody really had my interests at heart.”

Illustrator: Josh Freydkis

Consumers like her say that’s the real problem: Many financial advisers just don’t care what’s best for you. But with an industry awash in misconduct, the bigger issue may be that they aren’t required to care.

You’d be forgiven for assuming your relationship with a financial adviser carries the same sort of solemnity as, say, attorney and client or doctor and patient. An attorney is bound to zealously represent you; a doctor pledges to do no harm. So why aren’t financial advisers subject to the same duty? Well, the economics of the industry—fees, commissions, quotas—can end up standing in the way.

The Fiduciary Rule, finalized under Obama and originally set to take effect earlier this year, seeks to cure this disconnect. All advisers were to be required to put clients first when handling retirement accounts, where the bulk of everyday Americans’ savings reside. But then Donald Trump won the election, and on his 15th day in office, the Republican president ordered the Department of Labor to reconsider the rule. His advisers echoed Wall Street arguments that tying the hands of advisers would limit investor choices, raise the cost of financial advice, and trigger a wave of litigation.

SEC Chairman Jay Clayton

Photographer: Zach Gibson/Bloomberg

This Friday, the rule will take partial effect. Its future, though, remains deep in doubt. Many Republicans in Congress oppose it, and Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta has suggested that at the very least it be revised. Then last week, Trump’s newly appointed chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Wall Street lawyer Jay Clayton, announced his agency would also seek comment on the topic, a process that could further threaten the rule’s survival.

While Washington wrestles with the fate of the Fiduciary Rule, the financial advice landscape remains supremely dangerous. Three professors recently analyzed a decade of disciplinary data on 1.2 million financial advisers. What they found is decidedly unpleasant:

- At the average firm, 8 percent of advisers have a record of serious misconduct.

- Nearly half of those 8 percent held on to their jobs after being caught. About half of the rest got jobs at other financial firms. In other words, a year after serious misconduct, about three-quarters of advisers found to have wronged clients are still working.

- It gets worse: Some 38 percent of those misbehaving advisers later go on to hurt even more clients.

- You might think bigger firms would be more diligent, but you’d be wrong. At some large firms, more than 15 percent of advisers have records of serious misconduct. The highest was Oppenheimer & Co., where 20 percent had such black marks. Oppenheimer responded to the study, first published a year ago, by saying it replaced managers and made changes to hiring, technology, and compliance procedures.

- Predators typically seek out the weak, and financial advisers are no different: The study shows that those with misconduct records are concentrated in counties with fewer college graduates and more retirees.

The unique nature of the investing business makes it easier to exploit client ignorance. Investing is complicated, with sometimes-intentionally impenetrable jargon, and customers must trust their advisers in the same way they trust their doctors: If an expert makes a recommendation, you tend to follow it, whether that means getting heart surgery or a variable annuity.

“Some firms ‘specialize’ in misconduct and attract unsophisticated customers,” the researchers write.

More astute investors aren’t entirely at the mercy of advisers. Certain products are so expensive and so typically underperform that their mere presence in your portfolio can suggest you’re getting bad advice. Variable annuities, high-fee mutual funds, and non-traded real estate investment trusts, or REITs, are good examples. Non-traded REITs charge, on average, upfront fees of 13.2 percent, while delivering returns about half those of traded REITs, which are also much easier to buy and sell.

Another example is the “reverse-convertible,” a complicated product in which a bond payment is linked to the performance of a stock. Banks will create two or more versions of the same reverse-convertible. The only difference is one offers a higher payout—yet investors usually end up choosing the inferior product. University of Minnesota’s Mark Egan calculated that customers bought over 10 times more of a reverse-convertible with a 9 percent yield than an otherwise identical convertible with an 11.25 percent yield.

Why? Because that’s what their advisers told them to do. The more lucrative version paid advisers a commission of 2.15 percent, while the inferior one paid 3.09 percent. In other words, advisers could boost their pay by half if they steered clients to an obviously worse investment.

Commissions like these are the traditional way advisers hide costs from investors: Instead of clients paying them directly, companies pay advisers commissions to push their clients toward particular products.

“There’s an ever-present incentive to betray your client’s interest,” said Benjamin Edwards, a law professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. These conflicts don’t just cost investors more money. They also skew the U.S. economy by pouring capital into less productive investments merely because they offer a better “kickback” to advisers, he said.

A perfect illustration of this phenomenon occurred just before the financial collapse of 2008. Researchers conducting a study sent “mystery shoppers” into 284 Boston-area financial advisers. When clients walked in with the kind of low-cost, diversified portfolio independent experts recommend, only 2.4 percent of advisers approved of it and some 85 percent recommended making a change. Financial advisers were eight times more supportive if clients had a less-than-ideal strategy of chasing returns—one that was more likely to generate commissions.

Despite all this, the pretend clients didn’t smell a rat. In fact, they were smitten: Some 70 percent of them said they’d use the adviser to invest their own money.

There’s little reason to think things have changed. Finra, the private watchdog that oversees non-fiduciary advisers, barred or suspended 1,244 individual brokers last year, up from 843 in 2012. Clients still rarely know what’s going on, or what it’s costing them, industry experts said. Christine Lazaro, director of the free Securities Arbitration Clinic at St. John’s University in New York, said people who came to her just assume “the broker was doing what was appropriate.”

“They are always very surprised,” she said, especially by what advice was costing them. “The broker leads them to believe they’re not paying any fees at all.” According to a Cerulli Associates survey last year, a majority of investors in their 60s and 70s either aren’t sure what their fees are or believe incorrectly that they pay nothing for advice.

But paying they are. Offering financial advice is enormously profitable, with U.S. investment firms achieving operating profit margins as high as 39 percent, according to the CFA Institute. And once advisers collect enough client assets, they can get huge bonuses for switching firms (and bringing their customers with them). Until recently, the going rate was a bonus of more than three times the annual fees and commissions the adviser brings in the door; an adviser with $200 million under management could expect a bonus of $6.6 million. (The threat of the Fiduciary Rule, however, caused bonus offers to plunge.)

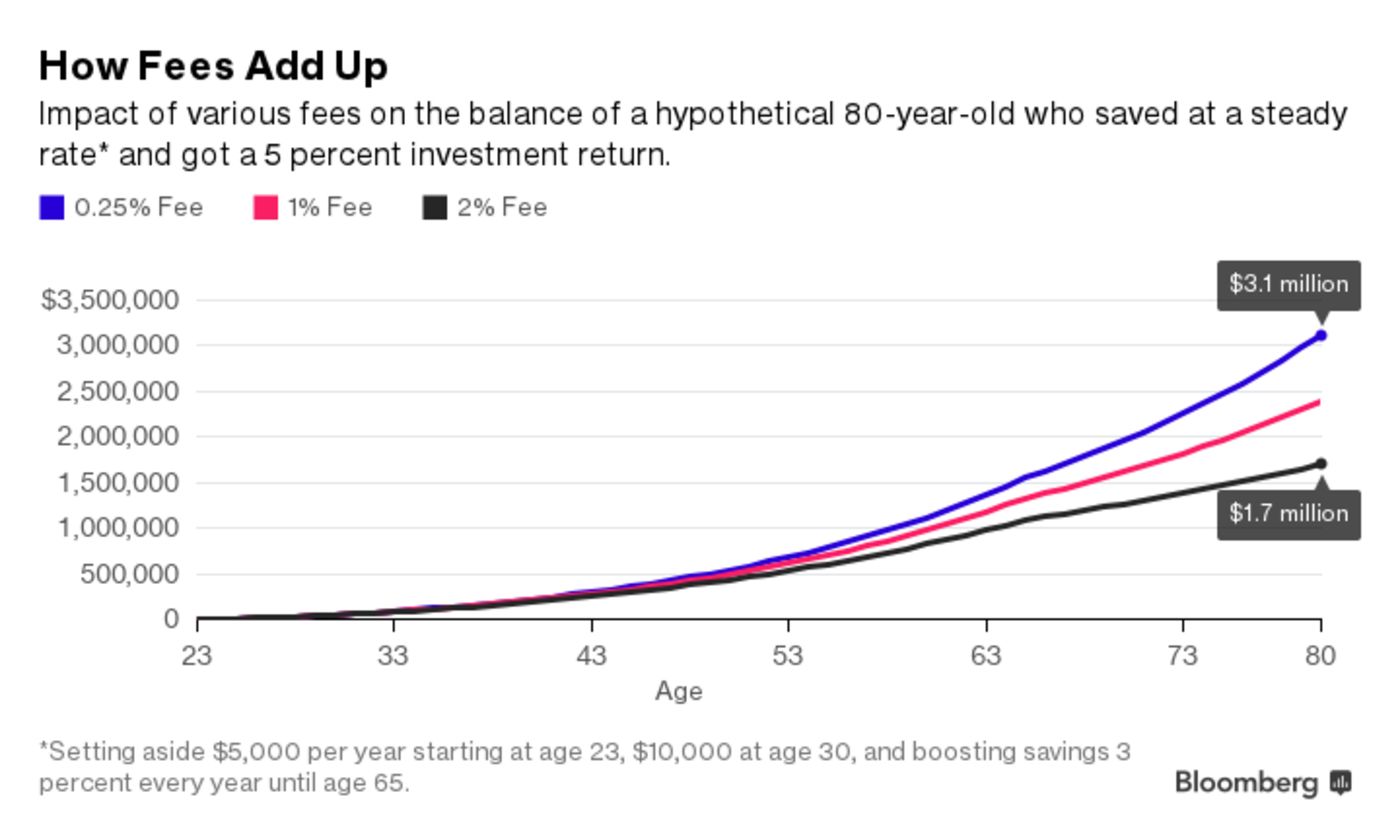

Meanwhile, the total cost of bad advice to consumers—in higher fees and lower performance—is probably much higher than the $17 billion estimatedby Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. The CEA figured investors are losing an extra 1 percent annually on $1.7 trillion in individual retirement accounts controlled by conflicted advisers. But IRAs represent just an eighth of the $56 trillion in financial wealth Americans control, according to Boston Consulting Group.

Illustrator: Josh Freydkis

Various academic studies show conflicts of interest costing investors dearly. One found that funds sold by brokers did 0.77 percentage points per year worse than funds bought directly by investors—even if you ignore some big broker fees. Another study compared investors advised by brokers with investors put in a target-date mutual fund. Those who got advice underperformed by 3 percentage points per year.

It’s hard to blame consumers for falling into these traps. The rules governing financial advisers could hardly be more confusing. While some are already fiduciaries, required to put their clients’ interests first, most advisers must merely recommend products that are “suitable” to client needs, a term open to wide and profitable interpretation. Making the whole thing more baffling, another group of advisers are “dually registered,” meaning they can act as a fiduciary or a non-fiduciary, depending on the situation.

Wealthy people, often pushed to buy faddish products with high fees and mediocre returns, aren’t immune either. Hedge funds perform poorly on average, while charging typical fees of 2 percent per year plus 20 percent of any gains. Then there are those structured products, such as the aforementioned reverse-convertibles. If advisers were required to put clients in the best reverse-convertibles—as a Fiduciary Rule could eventually demand—Egan calculates that investors’ risk-adjusted returns would rise by over 2 percentage points per year.

Wall Street argues that strict regulations on financial advice will make it less affordable for middle-class investors. The Fiduciary Rule “will adversely affect the ability of millions of Americans to save for retirement, increase the costs of retirement accounts while limiting access to advice and products,” the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association wrote in a letter to the Labor Department. But if advice as it currently exists is riddled with conflicts and hidden costs, supporters of the rule ask, does it even deserve to be called advice?

Betterment LLC Founder Jon Stein

Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg

“Lots of people are being sold products,” said Jon Stein, founder and CEO of online investment company Betterment LLC. “The ‘advice’ is almost nonexistent.”

In TV ads, firms tout their employees as trusted advisers, so close to their clients that they get invited to weddings. In arbitration hearings, the same firms argue they merely have an obligation to sell “suitable” products to these purported pals. A Fiduciary Rule would radically change this business—just the threat of the rule altered industry business models.

But the deeply entrenched culture of financial advisory firms also needs an overhaul.

The Fiduciary Rule will permit advisers to continue getting commissions (unlike Australia, the U.K., and other countries that have banned them). But it requires they charge reasonable fees, clearly disclose them along with other conflicts of interest, and show clients the best products available.

If fees were more transparent, it would be easier to shop around, and more obvious whether your broker’s advice is worth what it costs. Also, with a duty to put client interests first, advisers could get sued for recommending the most egregious investments. That puts pressure on insurance companies and mutual fund companies to come up with better products that appeal to advisers on their own merits, creating a virtuous circle. “Product issuers are going to be forced to compete on product quality,” Egan said.

But those hopes smacked into a wall on Nov. 8. “The Fiduciary Rule as written may not align with President Trump’s deregulatory goals,” Acosta, Trump’s labor secretary, wrote in an Op-Ed. “This administration presumes that Americans can be trusted to decide for themselves what is best for them.”

Advocates for investors are worried that the Trump administration is getting ready to gut the Fiduciary Rule. Now that the SEC is weighing in, a big concern is that both agencies will team up to create a new, weaker rule that allows brokers to call themselves fiduciaries with “no meaningful protections to investors,” said Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America. “That would arguably be worse for investors than the status quo.”

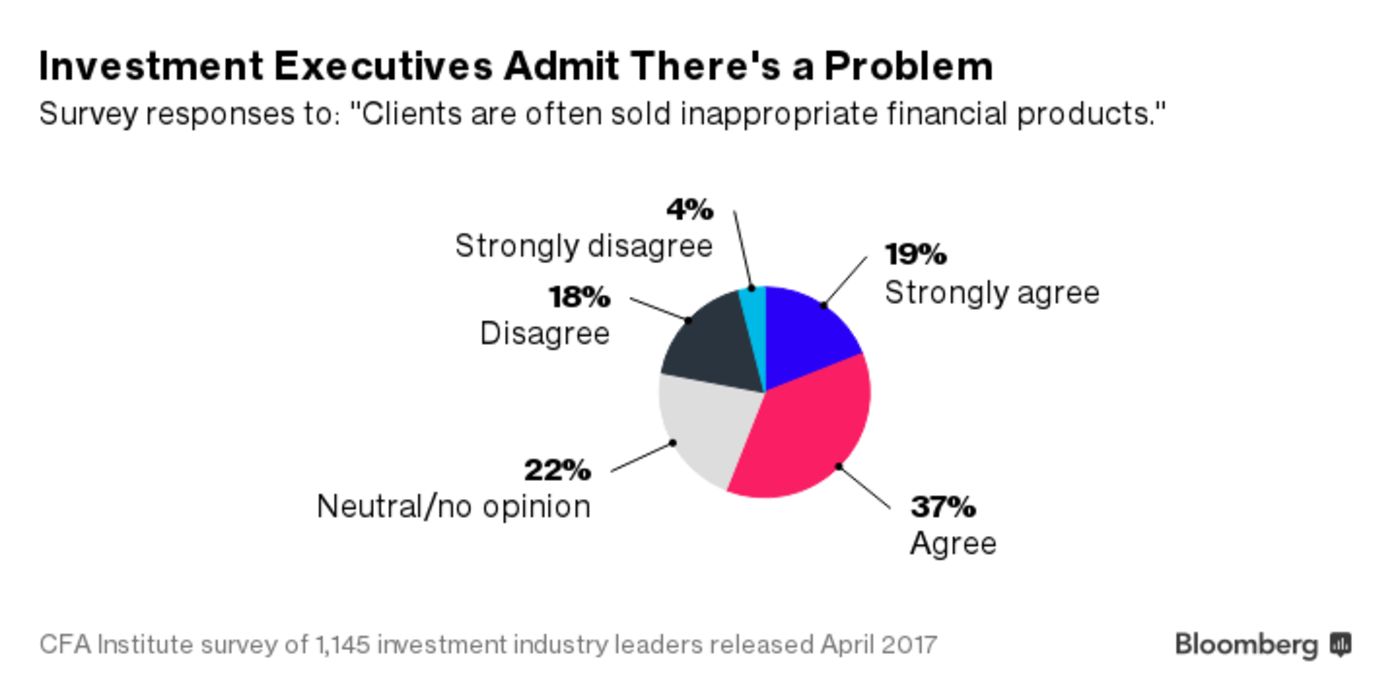

Though while Wall Street lobbyists fight the Fiduciary Rule, some individual advisers say they embrace it. “The image of the investment professional who always prospers—whether the client sinks or swims—has got to change,” said Paul Smith, chief executive of the CFA Institute, which represents 142,000 investment professionals worldwide, including an estimated 13,000 client-facing financial advisers in the U.S. and Canada.

“A lot of the industry has used the rule to put its house in order,” Smith said. That includes charging less. “Everyone knows we overcharge for what we do. It’s obvious.”

Even a majority of investment industry executives around the world concede customers are “often sold inappropriate products,” a recent CFA Institute survey found.

New, cheaper options have been driving reform as well. Technology makes it possible to provide advice to more people more efficiently. Betterment and Wealthfront Inc. are two of a number of startups called robo-advisers, offering advice and investment portfolios over the internet. Established firms such as Charles Schwab Corp. and Vanguard Group have launched competing products.

Shaffer, the Pennsylvania retiree, ended up moving her money to Betterment, where her portfolio costs her 0.25 percent of assets per year. She’s not the only one turning to cheaper robo-advice. Betterment, founded in 2008, manages $9 billion in assets, up from $6.5 billion at the beginning of this year.

To be sure, the Fiduciary Rule is no silver bullet. One regulation doesn’t automatically make advisers more ethical—the latest version of the previously mentioned misconduct study found no significant difference in misbehavior between fiduciary advisers and traditional advisers. CFA Institute’s Smith wants the SEC to regulate who can call themselves a financial adviser. Finra has stepped up enforcement with a new unit closely watching “high-risk” advisers, and is advertising to draw more traffic to BrokerCheck, a database that allows people to look up advisers’ disciplinary records.

But if the Fiduciary Rule is weakened or killed, much of the pressure for better financial advice may dissipate. Well-educated investors can usually find ways to get high-quality advice, but the more vulnerable will continue to lose out. And all advisers—even the most trustworthy ones—will remain under suspicion of being salespeople, not professionals.

Without at least the Fiduciary Rule, the phrase “trust your broker” could continue to be a punchline.